The Power of Association

How We Think about Power May Influence Our Ability to Do Good in the World

I felt his presence immediately, the man in pursuit. I had just left my friends at a festival and was headed home. To get there, I had to cut across a field and walk through town. As soon as I left the festival's perimeter, he was behind me. I don’t know why I didn’t turn and go back to the crowds of people. I suppose because it would have made me face him. Whatever the reason, it was just the two of us in an empty cornfield.

He was big, powerful, and menacing. I was none of those things. So, I just walked on, frozen inside and trying to set a fast pace to get me to the other side without looking like I was running away from him. We’re taught to hide our fear in dangerous situations, after all—as if only the evidence of fear triggers someone with malintent.

Eventually, I got to town. There, I thought, others would see what was happening and help. Or, at least, I could lose him. We rounded a few corners when I got the idea to enter a hospital building—or, rather, a building on hospital grounds. What I didn’t know was that it would be empty.

I headed down a long hallway. He walked slowly behind me as if he knew. That door at the end was locked. We would meet at last. I turned, saw his face, and tried to scream. But I couldn’t get it out. When I needed it most, my voice failed me.

Thankfully, this was just a dream. But it was telling, as I would later learn in a self-defense course for women. Many of us dream of being pursued by a dangerous man and finding we have no voice—of being overpowered physically and powerless to speak. That’s why our instructor had us practice screaming, so if we ever needed it, we would have the muscle memory.

I found myself thinking about this recently while reflecting on my associations with power—and how that might influence what we do in the world, the workplace, or even at home.

People Who Use Power Badly

When I think about power, I tend to think about people who use it badly. People like the man in my dream. People, male or female, who lord it over others. People who wield it deceptively. People who use power for their own ends, other people, animals, or places be damned. The worst politicians, oil barons, instigators of hate, and the like.

And there is, of course, good reason for this. The most dramatic, consequential, and best-known applications of power have often been terrible, even tragic ones. This is true across history and the present.

Robert Greene’s bestseller, The 48 Laws of Power, underscores this point. Random House describes Greene’s distillation of 3,000 years of the history of power as “amoral, cunning, ruthless, and instructive.”

But what does this mean for people interested in being positive changemakers—leaders who work to advance well-being, equity, the environment, or any other good cause?

It’s possible that if, as I have, changemakers have a negative—or decidedly mixed—view of power, that might undermine their ability to exert power for good.

People Who Don’t Believe They Have Any (or Adequate) Power

The psychologist Philip Zimbardo is best known for his controversial Stanford Prison Experiment. In it, he recruited male students and randomly assigned them to roles as prisoners or guards in a mock prison. The goal was to study the psychological power of roles, group identity, and more.

The study was criticized for both ethical and scientific reasons. But Zimbardo would go on to write a highly acclaimed New York Times bestseller, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil.

More relevant to this topic, he also later turned his attention to the other side of the equation—what makes people do good—and founded the Heroic Imagination Project, which trains ordinary people to help solve local and global problems.

Some years ago, after listening to a talk he gave about the idea of “ordinary heroism”—that everyday people can do extraordinary things—I spoke with him. It was a warm summer evening on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, and I wanted to ask the question that I had been asking any researcher who would talk to me:

“Why, given the seriousness of the issue, do you think more people don’t engage in climate action?”

Sporting his signature goatee, he responded without missing a beat: “Because everyone is told they can make a difference, and no one believes it.”

To my mind, that’s an overstatement. And yet, tone down the “no one,” and I think Zimbardo identified a vital truth.

Many people doubt they can make a difference regarding some of the most critical challenges of our day—from the decline of democracy to the climate crisis. There are many reasons for this. To cite just three: Knowing the great inequality of influence created by income inequality is one reason. Knowing that each of us is but one person out of 8.1 billion on the planet is another. And knowing that, in America, our political system has become increasingly corrupt is a third.

These and other factors are, to be sure, significant challenges to people who want to do good in the world. But we don’t need to voluntarily tilt the scales against us. That is to say, We don’t need to also undermine our sense of influence by believing that power is inherently bad.

People Who Use Power for Good

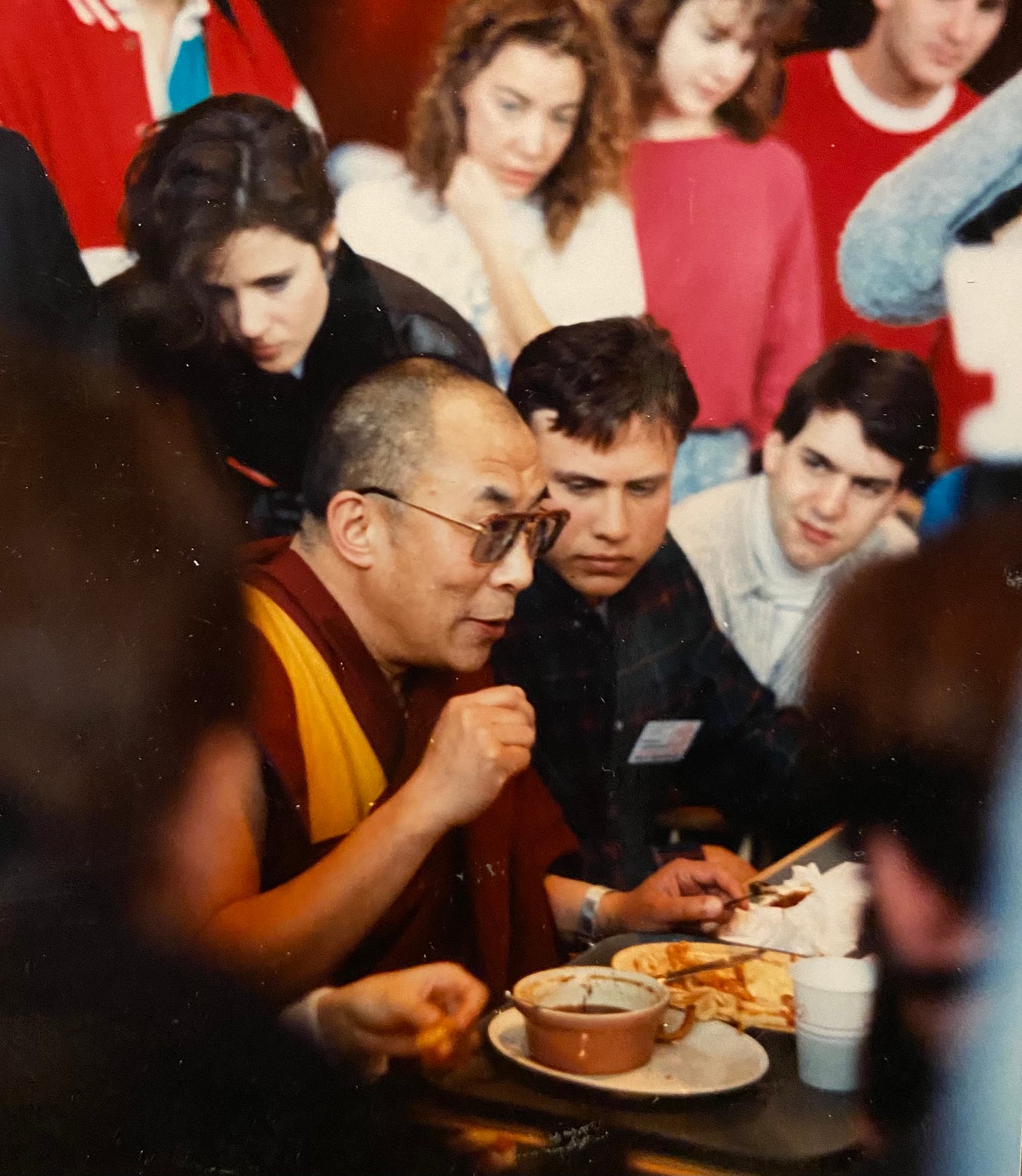

I once had the great privilege of reporting on one of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s visits to the United States. I was in a small group allowed to watch him descend from a plane in an airport near Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. I stood over his shoulder as he spoke with students at lunch. I was seated in the front row as he delivered a public lecture in a large cathedral. And I silently listened as he engaged in a more intimate conversation with faculty.

But the moment that seared itself in my memory is this one: Hundreds of people were lined up along a path, waiting to glimpse him as he walked across campus with the university president. I walked ten feet behind them, which gave me a vantage point for seeing the faces of the people as he passed by. I saw their faces before he approached, looking like people’s faces usually do: Some tired. Some excited. Some looked as if they had been waiting for a very long time.

Then, like a wave unfurling across a beach, their faces transformed. As they saw him come close, they suddenly looked peaceful and happy. He hadn’t said a word. They were responding to the power of his presence. To the power of his goodness.

It was an important lesson for me that real power is certainly not inherently bad (despite some inherent complications we can discuss another time.)

At its essence, power is neutral, like energy. The Oxford Dictionary defines it as “the ability to do something or act in a particular way.” What makes power good or bad, then, is the end to which it is put. Like fire, power can be used to warm and sustain life or burn and destroy it.

But I’m not sure we can create positive change in the world if we don’t believe in and fully embrace the power to do good.

P.S. There was something else I learned in that women’s self-defense course: How to drop to the ground when a person with bad intent grabs you from behind, escape (in this case) his grasp, and then use the strongest muscle group women have, our legs, to kick him clear across the floor. I must admit, that felt good.